Three years after its start, the Manx Y-DNA study is making slow but steady progress. More than 67% of the indigenous Manx family names are now included in this study, either fully tested or in part, and some new insights are beginning to emerge.

From our knowledge of Manx history we would expect the majority of the population to be of Celtic origin and have early connections to Ireland or Scotland. Also we would expect there to be a proportion of the Manx people who are directly descended from the Scandinavian settlers who occupied the Isle of Man one thousand years ago.

This indeed is the picture that is now starting to be seen in more clarity. Almost a quarter of the Manx population of 500 years ago were still of Scandinavian origin with the remainder of the population at that time showing genetic links to early families in Ireland and Scotland.

Scandinavian Origins: Preliminary analysis of the Y-DNA data is now also starting to provide some indications of when these earlier settlers on the IOM might have arrived from elsewhere. For example it appears likely that the present-day Cain, Keig and Oates families were all the descendants of one individual male Scandinavian settler who arrived on the Island around 1000AD. Their Y-DNA profiles are so close to each other that this is the inescapable conclusion.

We know also that the male ancestors of the Callow, Casement, Killip, Brew, Kinley, Kaighen, Karran, Kneale, Looney and Shimmin families probably all came from Scandinavia as well, and possibly in a similar time period. The Kaighen and Karran families are not closely related genetically although the possible similarity in the sound of their names might lead one to suspect that was the case.

Irish Roots: The Crellin and Garrett families (and probably Crennell) show a specific genetic marker which is more popularly attributed as defining the Uí Néill dynasty of early Ireland. Also Brideson and Quilliam show a particular marker which indicates an early origin amongst the Leinster Irish families. The Manx Crowe family show clear genetic connections to the O’Meagher family of Ireland also.

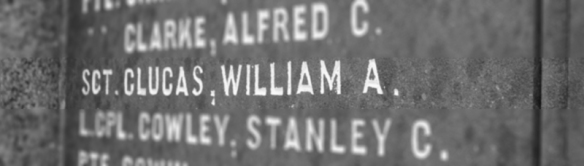

Scottish Connections: The Clucas family possesses a specific genetic marker which places their early family in Scotland. Similarly the Faraghers and Creers may also find some early connection in Scotland.

Others: There are also a number of other families (Kelly, Christian, Moore, Quark, Callister, Corlett, Gawne, Watterson and Morrison) which show Celtic DNA profiles, but at this stage the level of testing and definition is still not sufficient to be more precise about when and where from they arrived on the IOM.

What Happens Next?

A significant number of Manx families still remain either not fully tested or not tested at all and so more men are needed to take part! Important Manx families not yet involved in the study at all include Curphey, Hutchen, Kennaugh, Kennish, Kinrade, Kerruish, Kinvig, Kissack, Leece, Maddrell, Quayle, Qualtrough, Teare and Sayle. A number of other families are partially tested with, in most cases, just one more man being required to clarify the individual Y-DNA profile for that family.

So any Manxman who is interested in this study and wishes to take part should check the website at www.manxdna.co.uk and see if his family name is covered.

It is expected that the study will require a further 2-3 years’ work before enough families are included to justify a conclusion and broadcasting of the results – and in that time further knowledge of the detailed structure of the male genetic tree will become available as well as new analytical techniques. It is hoped that greater insights into the precise timing of the arrival of individual families on the Isle of Man will also become possible.

So we would welcome anyone who is interested in supporting this invaluable project, either by including a male family member for testing or even by providing some financial support for others to be tested. If you wish to help contact John Creer via the study website at www.manxdna.co.uk

A full copy of the Three Year Report can be seen here:-

http://www.manxdna.co.uk/3%20year%20report.pdf